One More for the Offshore Basket: An Orphaned Microcap Driller

A high torque offshore play and some broader thoughts on my current favorite sector

Disclaimer: Nothing on this blog is intended as financial or investing advice. Please do your own due diligence.

Earlier this year, as some of you know, I spent a lot of time looking at publicly traded real estate. The motivation to do so was straightforward: in many names, particularly those with office exposure and/or (optically) high leverage, underlying fundamentals (backed by supportive macro tailwinds) and stock prices were moving in entirely opposite directions. The divergence was one of the most ludicrous I’ve ever seen. That theme has worked extremely well for me so far, with each of my three picks (HHH, JBGS, and CLPR) handily beating the market. While I remain long, and think the forward returns continue to look very attractive for these three, I’m certainly not seeing the same value in the sector today that I was in June.

Fortunately, the market is giving us another opportunity to buy a sector with share prices that have become utterly decoupled from underlying fundamentals — viz. offshore drillers.

A quick word for those unfamiliar with the space:

I find it helpful to think of offshore rigs as floating real estate.

Offshore drilling rigs are high cost of construction, high operating leverage assets that are leased to offshore oil and gas well operators at contracted dayrates (e.g. Shell might lease a rig owned by Transocean for 2-years at a daily rate of $300k). Dayrates, like rents in real estate (and all prices in free-markets, theoretically) are determined by supply and demand. As the utilization of rigs increases (i.e. as more rigs are put under contract), dayrates follow, as well operators are forced to pay up to secure the remaining limited supply. Because of inherently high fixed-costs, drillers have tremendous torque to higher contracting rates (and inversely, margins can quickly go negative when demand drops). Historically, the sector has been viciously cyclical as high dayrates may justify the IRRs on building new rigs, which in turn eventually puts downward pressure on dayrates as the market gets flooded with new supply. And so the cycle goes.

However, for reasons that I will canvass more below — viz. steep and persistent discounts to replacement cost and increased rationalization through consolidation — I believe the harshness of offshore cycles is likely to be curtailed ahead (although not without some inevitable volatility over shorter time horizons).

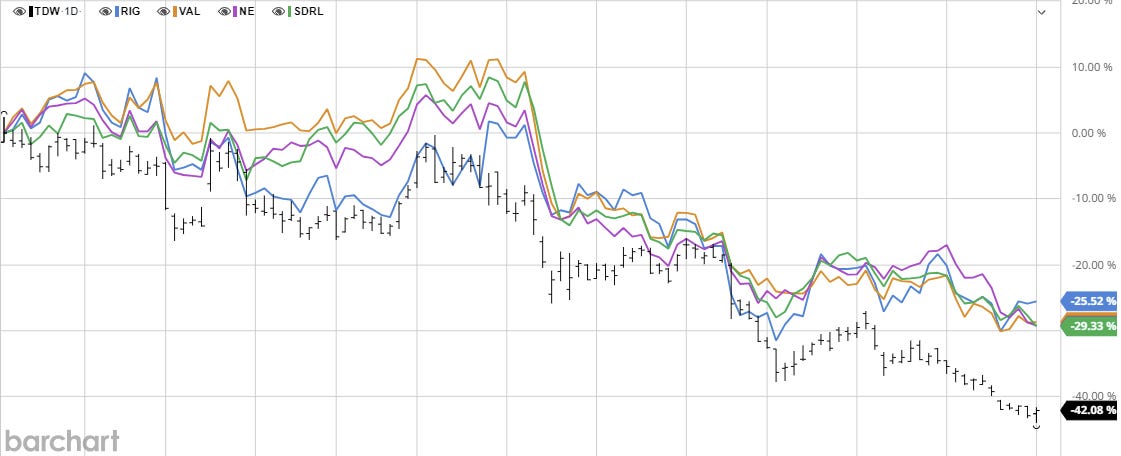

My biggest position heading into 2024 was Tidewater (TDW), which although a provider of OSV’s (not rigs), is largely subject to the same industry dynamics and contracting structures (and much of this write-up is equally apposite). I first purchased shares in and around September 2022 in the low $20s and the stock was a huge contributor to my success in 2023, exiting the year at ~$70/share. TDW continued to perform well into this year, reaching a high of $111 in May. Since then, however, TDW, along with practically every other name in the sector, has been completely hammered:

As you can see, since TDW’s peak on May 7, shares are down more than 40%, while the drillers (coming off much lower peaks) are down some 25-30%. Meanwhile, over that same period, the S&P 500 has returned ~13%.

What happened? Obviously, data started emerging indicating the offshore thesis was broken, right? Dayrates are in steep decline? Utilization is plummeting?

Nope.

Twitter user beentherecap highlighted three reasons for the sell-off in a great tweet this week, which I would parrot here. I agree with his assessment, both of the causes and their benignity.

Concerns around the supply and demand picture

During Q2 reporting in August, industry players began noting a slow down in dayrate momentum attributable to delays in expected drilling activity. TDW revised its FY revenue guidance slightly from $1.4-1.5B to $1.39-1.41B, noting they now expect “several drilling campaigns to begin later during the third quarter and early into the fourth quarter than originally anticipated”; Valaris likewise lowered guidance, noting “the current available opportunities for short-term gap fill work are now starting during the fourth quarter”; you can find similar comments of short-term momentum slowing in commentary from other industry participants.

These comments caused a broad sell off in the sector, but one that, in my opinion, is wildly overdone and myopic.

The perplexing thing is that the guidance revisions were small and management teams were adamant that the slowing of dayrate momentum is attributable to projects being pushed back a couple months, and not due to wider cyclical/structural issues with demand. Granted, it’s not as if management teams in the offshore space have never set expectations that fail to pan out. But their comments align with public industry data surrounding dayrates and utilization; leading edge dayrates for floaters are exceeding >$500K (see e.g. here and here) while active utilization is in the high 80s-low 90s% (see e.g. here and here). Contracting activity continues to head in the right direction:

Despite a rapid uptick in dayrates, newbuilds remain scarce and rig reactivations are slower than expected, “which makes us believe higher dayrates are highly likely, especially in late 2025 or 2026,” Evercore wrote. “We anticipate contracting activity, which was somewhat slow in 1H24, to recover as the robust FID pipeline translates to fixtures, further tightening rig supply.” …

Evercore said that contracting activity in the first half of 2024 has been somewhat slow due to 1) capital discipline and stakeholder alignment complexities, 2) supply chain constraints resulting from the sharp rise in global project backlogs over the past few years, and 3) E&P consolidations. The backlog for the deepwater rigs will likely remain flat into 2025 before recovering in 2H25.

[Source]

Meanwhile, the supply side of the equation continues to be supportive of strong fundamentals. Currently, ~90% of active floaters (drillships + semi-subs) are under contract, with very few idle rigs available to meet incremental demand before the market would need to turn to the cold-stacked fleet, reactivations of which are expensive (perhaps entirely uneconomic in many cases) and time consuming.

Moreover, there is virtually no order book for new rigs, as the existing fleet trades well below replacement cost and dayrates are no where near high enough to justify the cost and time needed to build one. Numbers here vary, but the general view is that the replacement cost of e.g. a 7G drillship is >$1B USD and would take 5-years to build, the economics of which would require a view on ~$800K day-rates being sustainable. It’s important to remember, of course, that replacement cost will only go up over time, illustrating the benefits of buying assets with high, but already incurred, construction costs with relatively limited ongoing capex needs, in an inflationary world.

So, we aren’t building new rigs anytime soon (and very possibly ever) and, in fact, an increasing number of older rigs are being retired and scrapped (see e.g. here and here)

And crucially, rapid ongoing industry consolidation is likely to ensure rationality with respect to contracting and the idling/retiring of rigs where necessary. More than 3/4s of floaters globally are owned by the big 4 of Transocean, Valaris, Noble, and Seadrill, with that number recently increasing as a result of Noble’s acquisition of Diamond. The consolidation trend appears poised to continue, with murmurs now emerging of a Transocean/Seadrill merger. This deal would be huge for the industry, effectively creating an oligopoly (3 players controlling >75% of floaters) and all the good stuff that comes with it.

Weak Oil Prices

The second reason for the sell off is likely due to declining oil prices, which is related to the question of demand. I will not spend much time here beyond stating that this is myopic in the current environment. Offshore services demand is a function of offshore capex, which in turn is a function of long-term oil prices, not of spot prices — E&P’s (unlike many financial investors apparently!) do not make offshore investment decisions based on where oil prices will be tomorrow. And in any event, the vast majority of offshore reserves are economic at oil prices well below today’s spot:

Momentum

The final driver of the sell-off is simply momentum/technicals. If you accept anything that I laid out above regarding supply/demand fundamentals, then it becomes clear that this factor is likely responsible for a lot of the price action recently (i.e. it’s not fundamentals based). If so, the market is providing us with a gift, just as it did with real estate earlier this year. Eventually, this momentum will turn, and I expect it to lead to a large sector rally, as prices have a long way to go to catch up with fundamentals. No one knows when that time will come (though a RIG/SDRL merger might be our near-term catalyst), of course, but absent the emergence of a recession or an immense collapse in oil prices, I am quite confident it won’t be too long.

I have continued holding ~95% of my initial TDW position, but have also gone long a basket of drillers over the recent months, including Transocean (RIG), whose extremely levered balance sheet of mostly asset-level/non-recourse debt has generated concerns that rhyme in many ways with those that surrounded REITs like Vornado, JBG Smith, and Clipper before they took off, and the warrants in Valaris (VAL), which offer a way to create similar torque on a far cleaner balance sheet.

There is a lot of online about VAL and RIG, and I don’t think I’d add much value in writing them up, though I do think they make for highly attractive investments at today’s prices.

So I figured while we’re at it I’d pitch another name in the space that I am long, which (for understandable reasons) gets far less attention than the others: it’s Norwegian listed Northern Ocean (NOL.OL).

This stock is not for the faint of heart (NB: it’s a foreign listed microcap with limited liquidity and a troubled balance sheet; the bid-ask here is often wide; please you use extra caution, DYODD, etc.), but it may have materially more upside than these other names if the story plays out as I anticipate I think it warrants inclusion in a broader basket of offshore names if you like the theme. And for those of you who would prefer to stick entirely with the leaders, what follows below may nonetheless be instructive. Again, I’m long the theme generally and that is ultimately more important than the specific names in my view.

Northern Ocean

Here’s why I like the setup:

Simplicity: Unlike the larger drillers, NOL is an extremely simple company to understand. It owns two sixth generation harsh environment (HE) semi-submersible rigs - Deepsea Mira and Deepsea Bollsta. That’s literally it.

Quality Assets with Improving Fundamentals: With an average age of 5.5 years, Mira and Bollsta are newer and higher spec than much of the global fleet, and are accordingly some of the highest quality rigs in the world. Moreover, supply and demand dynamics for HE semis are uniquely strong, augmented by higher barriers to entry due to HE/Norwegian regulations and a completely non-existent order book.

Valuation: We are creating the rigs for very cheap. At ~7.15 NOK/share, we are paying ~$320m per rig. Conservatively valuing them at $400m, (which is approximately what NOL paid to purchase them out of distress ~8 years ago!!) results in ~13NOK/share, or ~80% upside; valuing the rigs at market prices results in upside ranging anywhere from 100% to 300% depending on the comps.

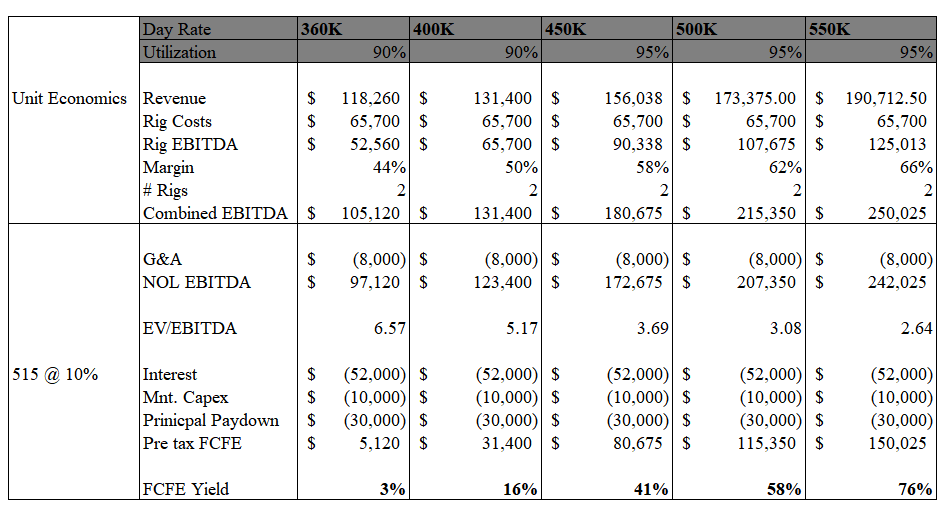

Further, if and when the rigs secure new contracts, the stock is incredibly cheap on a FCF basis; at $450K day-rates, well below the leading edge of $500K, the FCF to equity yield is >30%; at $500K, we are looking at a going in yield of >50%.

Leverage: Following a recent recapitalization, net debt is ~$450m on an EV of ~$640m. Though this debt poses some risk for reasons addressed below, it creates a lot of juice for the equity whether deleveraging through cash flows or asset sales.

Insider ownership and incentives: The company is 54% owned by shipping billionaire John Fredriksen. Minority shareholders are skeptical of him following a series of dilutive equity issuances, though the capital was probably necessary and largely improves the story going forward. Promisingly, a series of other insiders participated in the recent raise (at 7 NOK), and the new CEO and experienced management team are financially aligned. This provides some comfort against further dilution risk.

The Company

The offshore sector famously experienced a violent downturn in the mid 2010s as exuberance led to a large order book for new rigs which coincided with collapsing oil prices and a decline in drilling activity. As a result of their inherent operating leverage, and the financial leverage taken on to fund new rig orders, drillers experienced immense distress, with many eventually filing for bankruptcy.

Northern Ocean’s history begins in 2017, when John Fredriksen launched a company, Northern Drilling, to purchase newbuild rigs stranded at shipyards out of distress.

Fredriksen’s first purchase was Mira from a South Korean shipyard for $360m in early 2017. Seadrill, also controlled by Fredriksen at the time, had agree to pay ~2x that price to construct the rig (>$700m), before running into distress.

Fredriksen then purchased Bollsta for $400m later that year. Apparently, the construction cost of the rig exceeded $850m.

Obviously, readers should take note of the fact Fredriksen paid a combined ~$760m for the rigs some 7-8 years ago ( or a ~20% premium to today’s EV) when utilization rates for these ships were in the low 80% and dayrates were $300K. And yes, combined building costs were ~$1.5B (>130% of today’s EV). The numbers are even crazier once you adjust for inflation.

Fredriksen bought these rigs outside of Seadrill due to the latter’s ongoing distress, with the intention of later consolidating Northern Drilling. However, Seadrill was unable to avoid bankruptcy, and the two rigs were eventually spun out into a standalone company — Northern Ocean. I lay this out for context as to why this odd security exists in the first place.

What are we Actually Buying?

I think we investors might do better occasionally getting away from our screens and contemplating what it is that we actually own. I would recommend watching the first few minutes of this video just to get a sense of the magnitude and complexity of the assets which we are acquiring here (at a fraction of fair value, I would add). These are some of the most impressive feats of engineering and construction mankind has ever amounted to, perhaps outside of space exploration.

Mira and Bollsta are Sixth Generation Harsh Environment (HE) semi-submersible rigs. Though not limited as such (these rigs are flexible to work across many environments), these rigs are specifically designed, as the name suggests, to operate in harsh environments like the North Sea, Arctic, Canada, and the west coast of Australia. Due to the higher specifications required to operate in these conditions, and in some instances strict regulatory requirements (as in Norway), there are higher barriers to entry in this submarket. If you want a well drilled in these regions, this class of rig may be your only option. As a result, HE semi-subs tend to fetch premium dayrates in the market.

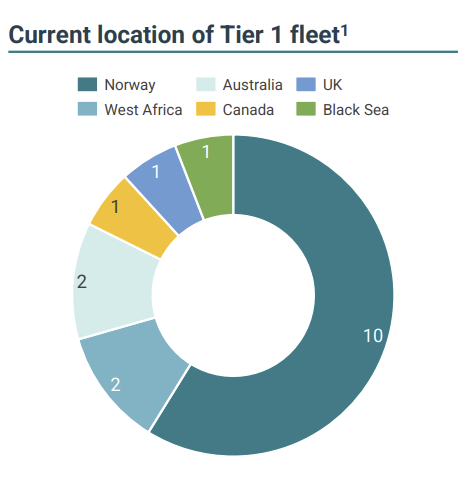

But here’s the thing is: there are very few HE semi-subs in the world, and even fewer of the modern Tier 1/6G class. Indeed, there are less than active 30 HE’s, and of that number, ~17 are Tier 1. And within Tier 1, Mira and Bollsta, delivered in 2018 and 2019 respectively, are of a handful of the most modern, high-spec in existence:

But scarcity and complexity alone aren’t sufficient for quality, of course — we need sustainable scarcity and demand for it.

With respect to demand…well, there’s a lot of oil in the North Sea (and no other way to get it out). Currently, despite the UK Labour government’s (short-sighted, and I suspect short-lived) restrictions offshore activity, there is still demand from already licensed projects, as well from Norway, which is the principal source of demand for these assets:

As you can see, some >50% of the active fleet is required just to serve Norway’s demand. And well over of half the Tier 1 fleet currently operates there:

Throw in demand from the UK, and growing activity on the west coast of Africa, where excess rig supply is being sent (remember, these are flexible across basins), and what you get is a market with >90% utilization and ~$500K leading edge day-rates.

So, there’s demand for our scarcity — is it sustainable? Absolutely. In fact, scarcity is improving.

For one, many of the older non-Tier 1 rigs are increasingly being retired and scrapped. Moreover, by my count, there are less than 4 high-spec, HE semi-subs currently under construction — and these are legacy orders from over a decade ago and may never actually end up online. Significantly, there has not been a single order for a semi-submersible in over 10 years:

(Note, again, how few HE’s are as modern as Mira and Bollsta).

And again, at the risk of repeating myself, that lack of order book isn’t about to change. By most estimates, a newbuild today would cost ~$1B, require a 50% down payment, and take some 4-5 years to bring online (pg. 43). Current rig valuations are not remotely close to justifying this investment.

As a result, we are left with the beautiful dynamic of increasing scarcity (ensured by inflating replacement costs) against assets that are necessary to satisfy demand:

Given Mira and Bollsta are more modern than much of the supply, they are benefactors of this declining supply schedule over time.

Naturally, given the dynamics I just laid out, utilization for HE semis is very high, with the vast majority of the fleet already contracted out (or at least optioned), through 2026 and beyond:

Alas — there’s a small problem: both Bollsta and Mira are without contracts looking out beyond the start of 2025 (NB: Bollsta has since secured a short (~30 day) contract to fill part of the gap in 2024 at $440K dayrate.)

The Opportunity

Why, if these rigs are so great, are they some of the very few without contracts?

For one, NOL’s fleet is managed by Odfjell Drilling, who owns its own fleet in addition to the fleet it manages. Here’s the backlog for its owned fleet (think there might be some incentive problems?)

Second, Bollsta was due for its 5-year Special Periodic Survey (SPS) this year (essentially scheduled maintenance), taking it offline.

The third thing I would point to is the pushing out of demand discussed above.

Fourth, and relatedly, is a game theory issue plaguing the industry. That is — the consensus is that demand, and thus day-rates, are likely to start accelerating in the back of half 2025; thus, rig owners are reluctant to lock themselves into long-term contracts now, at rates that may soon be below market. The additional tension with this dilemma for NOL is that, due to point 3 (pushback in demand), there is not a ton of short-term work to fill the gap — and given negative operating leverage and a suboptimal balance sheet, this is a problem.

Which brings me to the final point — the balance sheet. I suspect counterparties have been apprehensive about entering into contracts with NOL due to liquidity issues. NOL’s recent recapitalization helps assuage this concern — but is the company out of the woods?

The Refinancing and Private Placement

Liquidity issues and the limited backlog make this setup hairy, but it is also our opportunity provided we can get comfortable with it.

As recently as late May, NOL was trading for ~10NOK/share. Then, in June it announced a private placement of 90m shares at 7NOK to facilitate the refinancing of its debt. The transaction was highly dilutive, but necessary to address its upcoming maturity wall. Here is how it played out:

Hemen (Fredriksen’s trust and NOL’s largest shareholder) was issued 43m shares;

Hayfin (the second largest shareholder) was issued 19m shares;

Insiders/employees of NOL subscribed as well;

Sterna Finance (another Fredriksen entity) who held a convertible, exercised its right to convert for 30m shares at ~5.50NOK.

Due to the convert and private placement resulting in Fredriksen owning >40% of the company, Norwegian law required him to put in a mandatory bid for the remaining shares at 7NOK. An independent review found that 7NOK did not represent fair value. Notwithstanding, ~20m shares were tendered in the bid. As a result, pro forma the private placement, Fredriksen (through Hemen) owns ~54% of NOL, while Hayfin holds ~21%.

Obviously, this transaction was extremely dilutive. Shares outstanding practically doubled, with the issuance occurring at a huge discount to intrinsic value. But for new shareholders, there are positives worth considering:

The capital was necessary to fund Bollsta’s SPS and to clean up the balance sheet (more below); this eliminates not just the overhang of the maturity wall, but augments NOL’s ability to secure long-term contracts;

Leaving aside Fredriksen, the participation in the offering by Hayfin (who was nevertheless diluted) and numerous insiders, not only signals confidence in the outlook, but disincentivizes future harmful dilution.

As for the refinancing, here are the details:

Altogether, here is snap shot NOL’s capitalization at today’s share price:

The Path Ahead

As we can see, the refinancing ultimately extends NOL’s maturities — it does not eliminate them.

NOL requires ~$360K dayrates for each rig in order to hit cash breakeven. On a blended basis, Mira and Bollsta are earning >$400K for the rest of 2024, which should help generate some cash, but given Bollsta’s SPS cost, liquidity surely remains challenging. And with a contracted backlog of merely ~ $85m-105m, survival as a standalone company (absent destructive dilution) hinges on increasing that number substantially and fairly quickly. Whilst NOL surely could sell themselves in advance of their maturities, a distressed sale probably results in a discounted price for shareholders (albeit, one that still likely leaves value for the equity).

Having said all of that, I am not particularly worried about the prospects for these assets in securing long-term contracts at significant daydates, particularly with the inflecting activity in Namibia. The real challenge in my opinion, as alluded to earlier, is being able to find short-term, single well work to keep the rigs active through to the anticipated pick up in activity towards the end of 2025 and beyond. Bollsta’s recent contract with Springfield in Ghana, which could lead to further work, is a promising step in the right direction.

But ultimately the truth is, while I’m optimistic, the next 12 months are precarious and not without risk. It’s, however, a risk that in my view we are being well more than sufficiently compensated for given the quality of the assets and the very outsized upside that materializes from the multiple ways this might play out.

What are those ways?

Obviously, from a shorter-term perspective, the mere announcement of securing a high dayrate contract with some duration is likely to serve as a catalyst to send the stock (a lot) higher (math below). But looking at the bigger picture, there are two ways we can really get paid.

Selling the Rigs

NOL is significantly hampered by it’s lack of scale: Odfjell manages its fleet, exposing it to conflicting incentives, and with only two rigs, it has less assets across which to spread corporate costs and contracting risk. As is, it doesn’t make a lot of sense as a public company. And given both the enormous discount the rigs are fetching within NOL’s structure and a substantial leverage multiplier, a sale could result in huge upside to the equity.

Meanwhile, the industry continues to consolidate and NOL’s rigs are highly attractive assets that would immediately be valued at a relative premium within a scaled operator.

What price might they get in a sale?

Investors commonly point to the implied value of Odfjell’s similar — and materially older — fleet being ~$420m/rig. More recently — a transaction that has NOL shareholders very excited — is Transocean’s purchase of the remaining stake of the HE semi Norge at an implied $637m; Norge is as close as it gets to Mira and Bollsta (the same age, very similar UDW specifications); it is currently under contract for $510K/day, with backlog through 2028.

The below shows the per share value of selling the assets at: Northern’s cost of purchasing the rigs in 2017 ($750m combined), Odfjell’s implied value ($420m/rig); the Norge deal ($637m/rig); yard cost ($1.5B combined); and today’s replacement cost ($1B/rig).

Obviously, there’s probably no world in which these assets sell for yard or replacement cost — I include those rows simply to illustrate how far away we are from the economics of ever justifying building a new one of these.

Regardless, due in part to how levered the balance sheet is, you can see that selling these assets anywhere between Odfjell’s implied valuation and the Norge deal, results in a upside of ~ 100% to 320% to the equity. Significantly, we still make a good bit of money here even if the rigs were sold at Northern’s distressed cost basis from nearly a decade ago.

Even if NOL is unable to find contracts for these rigs and is forced to sell out of distress, it’s hard to see an outcome where the equity at ~7NOK gets materially impaired — that’s how cheap we are buying these. The wide gap between implied market values and NOL’s EV/RIG does give me some comfort around a margin of safety despite the liquidity issues.

Secure Contracts and Run the Rigs for Cash Flow

As much as I instinctively want a sale/liquidation to be the outcome here, the company’s recently appointed CEO Arne Jacobsen has indicated that the goal is to “build a strong order backlog, prepare for dividends, deleverage and participate in a much needed consolidation within the Harsh-Environment market.” Let’s bracket the consolidation piece of this for a moment. Assuming a strong backlog can be built in a timely manner, what does running these assets for cash flow look like?

The above is not intended to be precise, and is far from it. I’ve relied, in part, on assumptions from NOL’s own deck, though they appear reasonable based on my own review. I have also ignored taxes, which are contingent on where income is earned (and would obviously reduce these FCF numbers somewhat and change the breakeven point). The point of laying this out is to illustrate these key points:

We can see, as a result of embedded operating leverage, that as day rates head through 450K, NOL starts earning ~40% of its market cap in levered free cash flow. At leading edge day rates of ~$500K, the equity yields well over 50%. Clearly, securing a sizeable backlog in and around these rates will send the stock a lot higher;

But more so, there is huge upside to deleveraging. Currently, interest expense eats up 30% of EBITDA even at $450K day rates; debt amortization likewise eats a fair bit (albeit that is deferred for the next 12 months and can be paid in kind). The return on today’s equity price is crazy as the enterprise deleverages. Holding the enterprise value constant at ~$640m, every ~2m of principal paydown results in 1% accretion on today’s share price (or ~15% annual return based on the yearly amortization schedule). Moreover, if the company is able to secure a backlog of decent duration, I’d expect them to look to the bond market to refinance the debt. Assuming, for example, after some additional principal paydown from interim cash generation, that they refinance the whole stack and issue bonds at 8% with $450m of principal — that would save NOL $16m in annual interest expense, which increases our FCF number on $450K dayrates by some 20% before even accounting for reduced principal amortization. Again, this is all extremely imprecise and loose, but my aim is simply to show the earnings power of these assets, how high our going in yield is if market day rates are secured, and how much upside there is to the equity from merely deleveraging.

Based on this, one can understand management’s stated preference to secure backlog and start cash flowing to deleverage the balance sheet — the upside may well turn out higher than a sale (e.g. at 5x 500K dayrate EBITDA using today’s capitalization, shares are worth ~20NOK, or ~200% upside from here before accounting for any cash build/capital returns).

Okay, but what about management’s comment that they are looking to “participate in a much needed consolidation within the Harsh-Environment market?” I’ll admit when I first read this I interpreted it to imply participation as sellers, but based on this slide in their deck and conversations I’ve had, it’s clear that the (purported) intention is to be buyers of rigs held by single-asset companies:

My first thought was why would a sub-scale, two-asset company that is having its own assets valued at less than 50 cents on the dollar look to be a buyer of more assets? The second thought: how, with this balance sheet and a distressed equity value, are they going to finance it?

But those questions lend themselves to the answer: they will not, and cannot, look to be a buyer unless and until they secure a lucrative backlog and the math I laid out above starts to play out. At that point, the assets will be generating a lot of free cash and the balance sheet will be in much better shape; further, the equity will follow and re-rate, thus allowing it to potentially be put to accretive use as currency for these single-assets, which may well be available at a discount to NOL’s future EV/Rig.

In short, I am not worried about this ambition because it won’t be possible until we’ve already made a sizeable return on our investment.

All paths ahead hinge on securing backlog: if that happens, whatever management chooses — be it selling the rigs, or running them for cash and paying dividends or using that cash to pursue acquisitions — should result in a good outcome here.

Management and Incentives

NOL hired new CEO Arne Jacobsen in late August. He is very experienced in the offshore space having worked nearly a decade at Hayfin (recall, the second largest shareholder) and a few other companies. He was issued 6.5m options with a 12NOK strike and purchased ~1m shares at 7NOK. I may be missing some other equity comp.

Shortly after, NOL hired Eirik Sunde, Transocean’s former senior marketing manager for the Norwegian region as its Chief Commercial Officer. I take this as a signal that NOL is looking to improve its negotiating leverage in the region and reduce its reliance on Odfjell. He was later granted 1m options at a 12NOK strike, concurrent with identical grants given to the COO and CFO.

Overall, these appear high quality hires and the equity comp is an encouraging sign of alignment. This alignment is of course buttressed by the enormous insider ownership beyond Fredriksen, including Hayfin’s ~20% stake and the millions of shares held by directors and officers.

Risks

I’ll reiterate that although optically hairy, I do think there’s enough value in these assets that even if sold out of distress, they probably get a price sufficient to make the creditors whole without wiping much of the equity at today’s price; that said, one can never be sure of distressed outcomes and should thus proceed with caution. The specific risks are:

Failure to secure sufficient short-term spot work to fund operations and liabilities through to the likely late 2025 inflection;

That purported inflection does not come, and the rigs are not able to secure any duration at rates high enough to meet maturities;

Punitive dilutive financing to avoid distress and/or target value destructive acquisitions;

Global recession (in which case the entire sector sells-off, along with everything else).

Disclosure: I am long shares of NOL at an average cost of 6.52NOK. I am also long TDW RIG, and VAL.

Looks like it's the "Secure Contracts and Run the Rigs for Cash Flow" scenario so far. Pretty promising.

Nice writeup. I've followed the company for a while now and increased my position after the equity raise. Although painful, the raise was necessary and in my eyes decreased a lot of uncertainty going forward. A great deal for Fredriksson, getting more shares at 7.00 NOK before the rigs move to longer term contracts as West Africa transitions from exploration to production over the next couple of years.

The highlight here for me and that you pointed out, is that the Mira and Bollsta were bought for $400M a piece in a cut-throat environment, and the rigs were not even fully completed! NOL at a $650M EV today is a steal.