Where I'm Looking for Value Today

Today's frustrations are tomorrow's opportunity: some thoughts on small caps, biotech, coal, and an extended word on real estate

Disclaimer: Nothing on this blog is intended as financial or investing advice. Please do your own due diligence.

Quick note up front: This is a long and rambling post sharing some of the things that have been on my mind lately. I talk about a number of stocks and sectors in passing just to flag some ideas for readers, but these are not intended to be comprehensive stock pitches, nor is there any guarantee the information is accurate in all places. Pls DYODD as always.

***

“[1998, during the dotcom bubble] was the first year we lost money. We were down 5 percent, but the S&P was up 28 percent that year, so not a good year to lose 5 percent. In 1999 the market was up another 21 percent; we were down 5 percent again. In 2000, the market was down 9-10 percent, we were up 115 percent. We didn’t do anything different during those three years. The work we’d done in 1998 and 1999 finally got paid in 2000.” - Joel Greenblatt

I’ve been taking a fair bit of solace in passages like this recently as a reminder of the inevitable, but nevertheless frustrating, reality that markets are cyclical and rotational, and that periods of underperformance are inevitable even for the best of investors (some may recall Buffett being famously derided for losing his touch during the dotcom era, only to emerge with the last laugh after the bubble burst).

Now, I am not suggesting that we are in anything like the dotcom bubble right now. I don’t think we are at all. That said, it certainly hasn’t been fun watching indices surge to all time highs seemingly every day while nearly everything in my book has been down over the same period, giving back large parts of the material gains experienced earlier in the year. And I know I’m not alone here: indeed, only 17% of the S&P 500 constituents have outperformed SPX over the last 30 days; another way to view it: every couple days or so over the last month has seen more stocks in the Nasdaq fall to 52 week lows than rise to 52 weeks, despite the Nasdaq itself absolutely surging. The story has been even uglier in small-cap land, with the Russell 2000 down nearly 4% in a month and now essentially flat on the year.

Ultimately, it’s been a very frustrating couple months to be a stock picker. With nearly all the market’s returns being driven by a handful of megacaps, generating alpha has been an uphill battle.

But, to paraphrase Greenblatt again, “value investing works because it doesn’t always work”. As a value investors, we never want to invest pro-cyclically. We want to be short-term masochists because there is always reversion to the mean, and fortunes are made finding oneself on the right side of that reversion. And the reality is that there are currently an abundance of left for dead, deeply mispriced securities and sectors out there that are bound to generate substantial returns if and when that rotation occurs.

In sum: while it stinks being a value investor right now, it is this very reality that signals promise ahead. In this regard, I would echo Einhorn’s sentiment from his recent Sohn presentation:

“When I started in the business, everyone said Warren Buffett benefitted by starting his investment business when few people even read annual reports and few were good at valuing stocks. It was a shame that there was so much competition for me. There were thousands of experienced professionals trying to do the same thing. Well, guess what?

That’s how it feels right now. For the few of us who are left, it’s a great time to be a value investor. There is so little competition that the opportunities to buy fine companies with double digit cash-on-cash returns are more abundant than at any time in my career, other than at the bottom of a bear market.”

So where do we want to be when this approach begins to work again?

My thoughts.

Small Caps (in general)

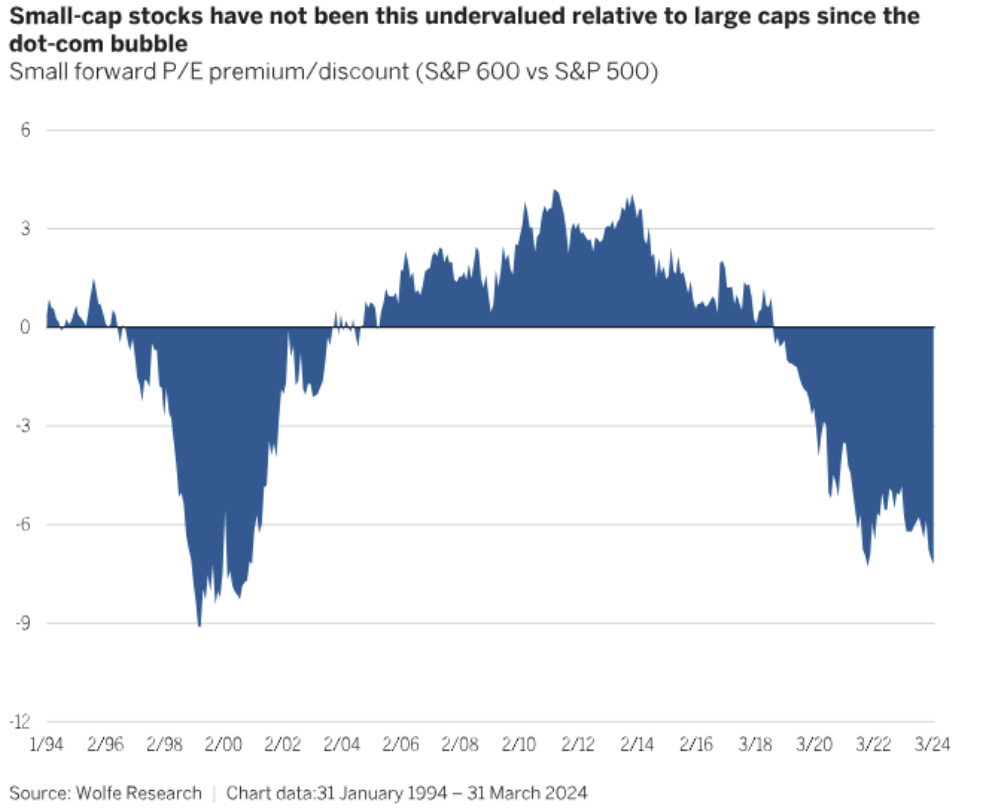

On a price/earnings basis, small caps are the cheapest they have been relative to large caps going all the way back 25 years to the dotcom bubble.

Obviously, like all things, there is an inevitable cyclicality here. But it the current period of large-cap outperformance now goes all way the back to 2011, which is longer than these cycles have historically lasted. At some point, things will turn, right?

Biotech

After a warranted collapse towards the end of ZIRP, the XBI is now essentially flat over the last 5 years. While there’s plenty of garbage in here, there is also a lot de-risked (relatively speaking) value for those investors willing to do the work. As has been the case with value as a factor more broadly, and likely exacerbated by the rise of the pod (and ranted about to some ridicule, though I think correctly, by Einhorn) there simply have been no incremental buyers to re-rate stocks absent a hard catalyst or return of capital. As such, there have been a number of biotechs reporting highly promising and de-risking late stage data that, in my view, have not remotely seen this upside priced in.

Some of you may have seen my venting on X about Mereo, a large position for me, which announced near perfect late stage data for its lead asset last week and is now trading below both its highs months prior to the data coming out, and more absurdly, its post-readout oversubscribed private placement price of $3.99 participated in by numerous hedge funds and insiders, including Rubric Capital, who controls half the board seats and owns some 15% of the company. Another example, of which I currently have no position, is Viking Therapeutics, which is now down some 40% from its February highs. The market, at the moment, appears unwilling to re-rate any biotech absent an imminent buyout.

Well, at some point, blockbuster drugs will get their value…

Cannabis

Another troubled sector filled with garbage, but which I have incessantly argued contains a few names that I think might become blue chip players in time. Alas, after being up nearly 100% YTD upon the DEA’s decision to reschedule cannabis in April, the MSOS index has given back nearly all those gains in the ensuing months for reasons that are not entirely discernible to me other than a cartoonish level of impatience and meme-like behavior by investors.

And the baby has been thrown out with the bathwater. Cronos Group, another very large position for me, is down ~20% from its highs and is now back to trading at essentially net cash: I continue to wonder how a growing, cash flow positive company with no burn and dominant market share in a nascent industry with such a large potential market can warrant an enterprise value of ~zero. But such is life right now. For what its worth, I think there are a lot of well capitalized companies in this space that could double or triple over the next couple years merely from regulatory clarity and improved sentiment.

Coal

I have been buying shares of Natural Resource Partners (NRP) and Peabody Energy (BTU) hand over fist. There is a “time-arbitrage” here so obvious that it ought to not be possible in anything but the most myopic of markets. There are two distinct but related ways to conceptualize this.

The first is time-arbitrage understood in the conventional sense: investors being unduly focused on the very near-term (e.g. current spot prices, China weakness, etc.) are creating a dislocation between share prices and intrinsic value. Anyone that has done the slightest work on either of these names is aware that each are set to experience a structural inflection in distributable cash flow that places them at ridiculous FCF yields looking 18-24 months out.

For NRP, that inflection is coming from the complete extinguishment of the onerous capital stack that has impeded its distributions to the commons for a decade. With the debt, preferreds, and warrants fully out of the way by some time next year, the commons should conservatively see a mid-teens dividend yield for years to come.

For BTU, that inflection is poised to come from the commencement of longwall production out of the Centurion mine by 2026. Last year, BTU returned $470m to shareholders, mostly via share repurchases, which is good for a >15% yield on today’s market cap. That alone is already attractive. But it’s far more attractive once we underwrite the additional cash flow Centurion should contribute as well as some ~$100m of capex savings once it comes online. Even underwriting material declines in thermal, I think we’re looking at > 20% yield in a couple years (and even more upside on a per share basis if the company continues aggressively retiring shares in the interim). What’s interesting is that even industry experts who are well aware of these economics tend to trade around the seasonality and short-term spot price movement that comes with these names. Personally, that’s not my game — I don’t mind clipping a decent yield while we wait for the inflection.

The second way to look at the time arbitrage here comes from the view that the market simply has the terminal values extremely wrong. With forward fcf yields that could very well be +30%, the market is telling us that coal is dead by the decade’s end. Surely, only those living in an ESG fairytale land believe this to be true, at least as far as it relates to met coal, which comprises ~75% of NRP’s coal revenue and will be the majority of BTU’s business pro forma Centurion. But one of the reasons I’m bullish on these names over a pure-play met producer like Warrior (which I also love) is that I think the consensus is likely out to lunch on thermal moving ahead, which would provide additional upside that is clearly not being priced in. On the demand side, there are two things to point to.

First, I think Westerners and ESG proponents tend to underestimate the incentives and priorities of those in the developing world. The reality is that environmentalism is a luxury of economic freedom; and for those that lack such freedom, the path to obtaining it will be fueled by cheap and reliable energy. I’ve done a fair bit of work on what the developing world’s demand for energy moving ahead might look like; there’s a bunch of good literature on it out there, and I’ll perhaps do a piece on this timely topic soon. But I think there’s a fairly good chance global thermal consumption stays robust for some time to come, as incremental demand from developing nations offsets declines in the developed world:

Indeed, just this week India announced its use of coal-based power has hit an all time high. Bloomberg also reported that India will look to add more new coal power capacity than it has in a decade

The second point which has been getting a lot of attention recently relates to the huge increases to electricity demand being brought on by AI. For some great insight into this theme, I recommend reading this commentary published last month by Goehring and Rozencwajg. Though the piece focuses on natural gas demand, the implications should spill over to thermal. A couple highlights:

There are basically three takeaways here: 1) AI requires a lot of power; 2) this need for power will not be mitigated by more efficient chips, because efficiency will be offset by complexity; and 3) green energy sources like solar and wind are not viable because data centers cannot run on intermittent sources of energy - thus, the demand must be met by traditional sources: natural gas, nuclear, and coal.

Of course, this surge in electricity demand has arrived precisely during a period when Western governments have done everything possible to deter and transition away from the use of traditional energy, particularly nuclear and coal.

US nuclear capacity (presently ~18% electricity), for which the environmentalist’s phobia against can be understood only as ideologically driven and which is shaping up to be one of the disastrous policy errors of the 21st century, peaked at 112 reactors decades ago and has come down to 93; the average age of these reactors is some +40 years; and with exception of the two reactors brought online at Georgia’s Vogtle plant in 2016 and this year, no US reactors have been completed in the 21st century. What’s more: construction for these reactors commenced in 2009 and cost more than $30B to build. Given this time and expense, and that there are no new reactors on the way, incremental nuclear capacity is not a short-term solution.

Most of the burden will fall on natural gas, which is presently in a large surplus. However, as G&H indicate, with both shale production declines and expanding LNG capacity, declining domestic supply may well likewise be insufficient to meet demand.

Altogether, this may mean domestic demand for thermal sticks around longer than expected. Over the last decade, coal powered electricity has declined by ~60%, though it still comprises ~19% of total electricity generation. With thermal production in steady decline and exports around all time highs, there’s a reasonable chance we see elevated or at least sustainable pricing for thermal for several years to come. In what is a twisted irony, it may be that a hated remnant of the old world is what enables us to fuel our transition to the new world. I think we see a slow and beautiful death for coal. If so, these stocks are going to be huge winners over the next decade.

Returning briefly to the conception of terminal value mispricing. I don’t believe that most investors genuinely think coal is disappearing by the end of the decade. Rather, a huge part of the undervaluation here stems simply from ESG and other marketing mandates that are preventing large swaths of capital from going anywhere near these equities. The dynamic is not limited to coal or even energy, though this perhaps where it most pronounced; other industries that immediately come to mind are tobacco and private prisons. If these areas don’t violate your conscience, I think this is generally an interesting theme to look for in this market as you often get a combination of low valuation and capital returns (i.e. high realized cash yield), bypassing Einhorn’s problem of the incremental buyer.

Real Estate

The final area I want to discuss here is publicly traded real estate, which I have been fixating on for a while now. While some names have held up well (mostly certain large cap multifamily REITs), REIT’s as a class have significantly underperformed, and certain names, particularly smaller caps and those with material office exposure, probably have some of the worst sentiment surrounding them in the entire market.

The reasons for this are obviously well-understood:

Rising interest rates have expanded cap rates, pushing valuations down;

There are a wall of debt maturities coming over the next couple years which in many cases are going to be difficult to refinance;

Those that are able to refinance are going to have their cash flow burdened by increased interest expense;

There has been overbuilding of multifamily capacity in certain geographies;

Office vacancies have exploded due to changes brought on by pandemic and many perceive the changes as an existential threat to the asset class.

Of course, because price drives narrative, the underlying reality often begins to turn well before share prices do. To paraphrase a common expression tossed around in value investing circles: “you make the most money when things go from awful to merely bad”. The lesson: buy cyclical distress before the cycle turns. I think we have that opportunity in certain of real estate names. Here’s why.

Inflation and monetary debasement

The emergence of inflation coming out of COVID largely precipitated much of the decline we have seen in the sector given rapid the increases in interest rates implemented in response. However, because, in part, our fiscal authorities have not found religion on spending (nor does it seem they ever will) there’s still a ton of money out there, which I think keeps inflation well above 2% as our new normal. One result of this spending recklessness is obviously that it pushes asset prices up, at least in nominal terms. So that’s a long-term tailwind for the sector. However, concurrently, because of how expensive housing is, many are opting to rent, which in turn drives up NOI absent a commensurate supply response.

But in many regions of the country, no such supply response has come because increased building and financing costs coupled with elevated cap rates simply make it too difficult to pencil out new developments in many parts of the country. This combination of factors should be bullish for multifamily in supply constrained regions. A couple examples in my portfolio:

Clipper Realty (CLPR) is a small cap REIT with properties exclusively in NYC, the majority of which are multifamily. NYC, which is a definitionally supply constrained market - a problem exacerbated by the perilous development environment — has seen rents skyrocket in the post COVID period. Have a look at both Clipper’s occupancy rates and rent growth trends over the past couple years. Seems fairly robust?

Now, you might say, the negative sentiment around real estate doesn’t apply to Class A NYC multifamily, the strength of which has not been lost on the market and is fairly priced given current interest rates. And while that is true, there are sometimes dynamics at play with publicly traded real estate that allow you to create your interest at an implied valuation completely disconnected from where you would be able to purchase such interests de novo in the private market (I will touch on this further below).

And NYC is not the only place demonstrating NOI growth. My other REIT, JBG Smith (JBGS), which operates primarily in the Washington DC area, ended Q1 with its multifamily portfolio 96% leased and saw region wide rental growth of +3%. Again, a product of inflation driven rental demand and depressed supply:

So there’s a great deal of strength in some areas of the country. But, in my view, the real insight comes from thinking through where this goes. If we fail to get our fiscal spending under control, which I think is likely, then we should see continued inflation driving rental demand; if NOI growth tracks 3% inflation over the long run, that’s obviously a huge upside to equity values once you factor in leverage.

Now, let’s imagine what happens when we cut rates in the face of this inflation…

Interest Rates Coming Down

This angle is fairly obvious, though as with most things in the market, no one seems to be in rush to get ahead of this catalyst. We don’t know when the Fed will cut, but we can be sure that they will at some point. The current expectation is that we see one cut this year, which some think is increasingly likely given some emerging weakness in the consumer. I’m not in the business of macro predictions, but I’d personally be surprised to not see one in advance of the election. Regardless, assuming you can identify businesses sufficiently capitalized to survive whilst we await a cut, I expect a fairly aggressive re-rating, particularly in office, where the looming maturity wall has made the sector untouchable for many.

Office, Leverage Concerns, the Looming Maturity Wall, and Capital Stack Optionality

Here is where I think things get very interesting. Approximately $2 trillion of commercial real estate loans mature in the next three years, with nearly 75% of that by 2025, of which some $300B relates to office:

Given the foregoing, the concerns here surrounding multifamily are largely limited to certain regions with weaker fundamentals like the sunbelt or to particularly overlevered assets. Fear in the office sector, on the other hand, which has experienced vastly diminished occupancy and declining valuations, is palpable.

But like all real estate, office fundamentals too are regional. Nor are all office assets capitalized the same way. Yet here again the baby has been thrown out with the bathwater, creating what I think is an incredible opportunity for investors willing to dig through the carnage.

Each of the three real estate companies I am long - CLPR, JBGS, and Howard Hughes (HHH) - have varying degrees office exposure. In many respects it’s a huge part of what makes their setups so attractive.

I’ll start with the easiest as it relates to the issue of office and leverage: HHH. This is one of my largest positions and has so many characteristics that I have a fetish for as an investor: 1) there’s an approaching event-angle with a spin-off of a hodgepodge of assets and the Seaport development and an accompanying rights offering being backed stopped by Bill Ackman (add in the absolute venom many investors have for these assets and Ackman, and I strongly expect we’re going to see some textbook Greenblatt dynamics here - I’ll definitely have more to say on this in the months to come); 2) a stock that has gone nowhere for a decade; 3) a business that is a really awkward fit as a public company (a non-REIT, with no capital return program, several segments and geographical focuses, and that is hard to grasp with GAAP accounting); and 4) some of the most cynical sentiment you’ll ever see, which has caused investors, in my opinion, to lose the forest through the trees (if you want any evidence (and a good chuckle), have a look at some of the vitriolic and totally backwards looking commentary on this VIC pitch.) This is not intended as a write up on the company so I won’t get into it, but I think a lot of very bright people are getting caught up in minutiae and letting a disappointing decade cloud what really matters here — viz. a collection of high quality assets with every tailwind imaginable trading at a deep discount to its NAV.

Beyond this, one reason HHH is so left for dead is that it has a lot of office exposure (nearly 7m SF) which comprises ~50% of its in place NOI and it optically has a lot of debt. But these aren’t remotely concerning issues in the case of this company. For one, at the present share price you’re getting the office portfolio for free (let’s bracket debt and cash flow needs for a second). More importantly, HHH’s office fundamentals look vastly superior to many parts of the country — this is due, in part, to HHH having a monopoly over the supply within its MPCs. Indeed, in Q1 the company reported a 10% YoY growth in office NOI as well as 88% of the total portfolio being leased. These are simply not assets with troubled fundamentals like we are seeing in other parts of the country.

On the debt piece, 85% does not come due until 2026, and the vast majority (~2.5B out of 5.3B) not until after 2028. They also have a ton of levers to pull - land sales (gross asset value of retained land bank is some 4B) operating asset sales, etc. — in the unlikely event they were to run into an issue down the road. In short, I don’t see the direction of interest rates in the short-term having any lasting impact on the long-run value proposition here — and yet in many respects the stock trades on short term interest rate moves. Opportunity, I think.

Now for JBGS. This is a REIT that was the spin-off of Vornado’s DC assets in 2017. The stock, which has traditionally been office concentrated, has been a disaster, down ~60% excluding dividends since going public. There are again office and debt concerns here that I think the market is being lazy with. For one, the company has been aggressively divesting its office assets over the years and recycling the proceeds into multifamily, the strong fundamentals of which I touched on above.

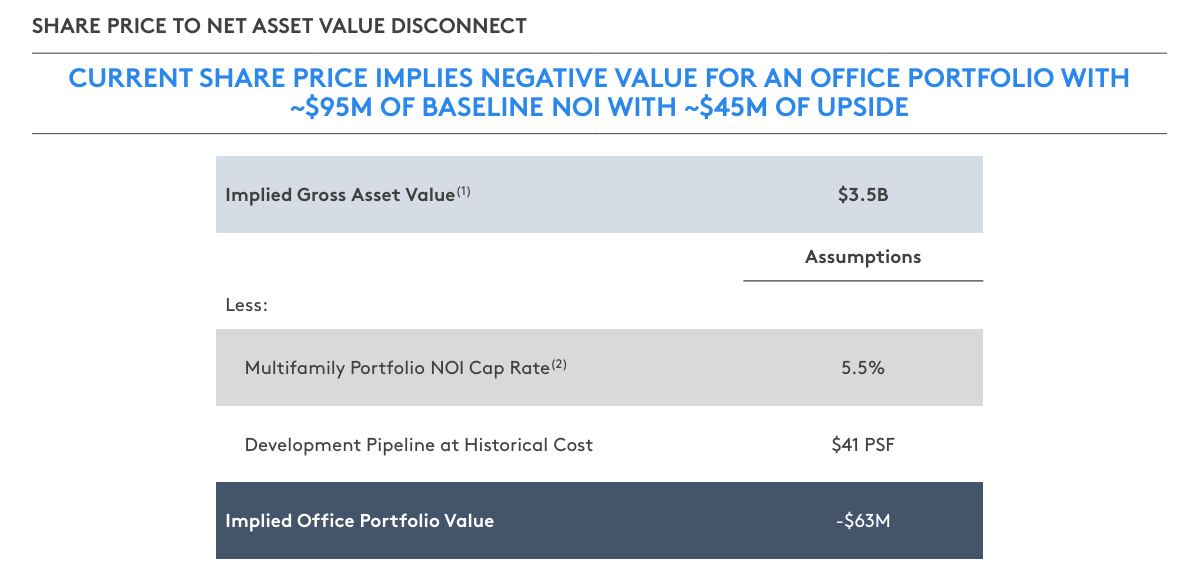

On an NOI basis, presently ~56% is office. But most of that is in National Landing, which has uniquely robust fundamentals (due to, among other reasons, JBGS, like HHH, also having substantial control over the supply) with ~83% occupancy rates, which should improve as they place additional toxic assets out of service. Further, at the present share price, we are getting the entire office portfolio for free (take these numbers with a grain of salt, but this is directionally correct):

The larger problem is that the company’s debt looks scary: Net debt/EBITDA is >9x, total debt is ~$2.6B vs. ~$230m cash (though there’s further borrowing capacity too), and ~$340m of office maturities and ~$850m of total maturities coming due by 2026. While instructive, ending the analysis here is plain lazy and I know that there are plenty of investors that see elevated net debt/EBITDA levels like this and simply move on.

Here is what I think a lot of people miss. Some REITs, like JBGS, are financed largely at the asset-level, meaning that mortgages are secured as against the specific asset but are non-recourse to the corporate level. Indeed, all of JBGS’s debt due this year is non-recourse as is the majority of it coming due through 2026:

What this means, in effect, is that JBGS commons have priority in the overall corporate capital stack over the lenders of much of the secured debt, because the latter is at the asset-level. And it is this particular dynamic that I think makes certain REITs so attractive in this environment: we are able, essentially, to create an equity interest in a portfolio of assets 1) benefitting from attractive legacy debt (cheap and high LTV) that would not be obtainable to a buyer of these assets today, while 2) largely insulating ourselves from the downside of that leverage given the risk is diversified across of portfolio of assets where the debt is not cross-collateralized or recourse to the c-corp. In other words, we get a call option on these assets surviving, without the commensurate downside to our equity given the large discount to NAV the commons trade at.

Now, there are certain implications with simply foreclosing on your toxic assets, such as taxes, but it’s a viable strategy in some instances and one that JBGS explicitly pursues. Once understood, you look at valuation by comparing the company’s public market capitalization against the private market value of the equity that results after subtracting both the NOI and debt of the forfeited assets. Looked at this way, JBGS’s valuation today is very cheap.

Perhaps the master of structuring debt at the asset-level like this is Vornado’s Steve Roth (thus perhaps explaining JBGS’s wisdom in pursuing a similar structure). Bill Chen (diehardcapital on X) shared a very instructive slide for conceptualizing this on X this week.

Clipper is the most fascinating and misunderstood use of this setup that I have come across. At first glance, Clipper looks laughably overlevered. At $3.60/share, the diluted market cap is $153m. Debt at cost, after subtracting ~40m of cash, is $1.2B. This mean only 11% of the $1.35B EV is equity. Meanwhile, net debt/EBITDA is a hilarious ~18x. Yikes, right?

Depends how you look at it.

It turns out that essentially all of CLPR’s debt is at the asset-level, but the commons do not seem to be reflecting that reality at all. We can see this because if you tally up the private market equity value in each of Clipper’s assets using run-rate NOI, market cap rates, and the existing debt stack, you’ll find that number far exceeds today’s market cap:

So the commons trade at > 60% discount to private market NAV — how is this possible? (I should note this overstates things as you need to capitalize ~14m of G&A, which at 8% would bring the NAV discount down, but still above 50%). Well, for one, you would never be able to get $1.2B of debt against these assets in today’s environment. On one hand, this illustrates how advantageous REIT structures can be in certain instances — we can capitalize on this attractive leverage profile to create an interest that wouldn’t be possible today. On the other hand, the market is telling us this capitalization is unsustainable and the company will need to put up far more equity to retain these assets once the debt matures.

While nearly all of CLPR’s debt matures after 2028, trouble might manifest far sooner with the tenant at 250 Livingston giving notice of termination for August 2025 (250, along with 141 Livingston, are the company’s two lone office properties, and there very well may be a termination at 141 coming soon). These are very challenged office assets given location and age, and there’s a very good chance they are unable to re-lease them and will have to foreclose. That’s about 23% of total company NOI. That will obviously impact cash flow and the dividend, which presently yields 10%, but given the non-recourse dynamic we’ve been discussing, it’s not going to zero the equity of the commons. Moreover, because the private market equity value of CLPR’s 3 best stabilized assets (Tribeca, Clover, and Pacific) as currently capitalized are essentially worth the entire market cap, there’s a ton of optionality for the company to foreclose on and/or divest the other assets before we have to worry about suffering a permanent loss on our investment.

This is not meant to be a comprehensive pitch — there’s a lot of hair here and I’m definitely leaving some important details out (such as the tax implications of foreclosure on Livingston, etc.) but it’s an interesting setup conceptually for looking at REITs in this environment. I shared some thoughts on CLPR here and I’m happy to discuss this, or anything else, offline.

Now’s the Right time in the Capital Cycle

The final point I want to make on real estate is simply that this is a cyclical industry in which investors have generally been greatly rewarded for buying things when they are cheap, hated, and below replacement cost. I’ll close this out with a passage from Steve Roth in his recent annual letter to VNO shareholders, which is a worthwhile read:

Amazing

great piece. To add on the energy section, secondary beneficiaries for increased electricity demand would be copper (transmission lines) and surrounding metals used in electronics to meet the needed throughput through the increased demand. Perhaps also land/regions that have cheap electricity will have some sort of pricing power, especially if they build data centers on these lands. Another interesting phenomena that could be seen is the dual use of bitcoin miners for mining bitcoin during bull cycles and using them as AI centers during bear cycles or just dual use depending on which has more demand