The Investment Case for Movie Theatres - Part I

A History of Cinema Exhibition and Its Recurring Cyclical Patterns

Disclaimer: Nothing on this blog is intended as financial or investing advice. Please do your own due diligence.

“In that downturn…things happen internally to businesses. They downsize, they right size, they consolidate…and therefore you get a much better business if it survives…and you get a competitive landscape that potentially changes.” - Bob Robotti on the Business Brew

In my last update, I indicated that my next piece would be another cinema company. However, in the course of doing research on this industry, I’ve been struck by something that may be more instructive to the thesis than anything about the company itself. Namely, it appears that over the course of the 100-year history of theatrical exhibition various intertwined cyclical currents have played out over and over again. Today, the set-up looks much like it has numerous times before, and I suspect studying those moments will be quite illustrative of where things are going.

So with that I am going to do something a little different this time around and publish this as a multi-part write up. Part I (below) will dive into the history of exhibition and extract any learnings we can take from it, and Part II will be the usual single stock deep-dive on a name in this sector. I realize this is optically poor timing given Trump’s latest missive, but the company I’ll be pitching is very unlikely to impacted by whatever comes of it, if anything (color me skeptical). I haven’t decided if there will be a Part III, but there is another name I am thinking about highlighting afterwards.

****

As readers will know from my Reading International write up, I think the cinema exhibition industry (movie theatres and related businesses, e.g., tech providers) is an incredibly misunderstood and, consequently mispriced sector that is set to deliver very strong returns in the coming years. The industry broadly makes for a fascinating discussion and a good case study on how businesses and industries can evolve in the face of challenges, even secular ones, to emerge improved and more profitable than they went in.

It’s hard to think of an industry enduring a more existential threat than cinemas did during the pandemic, which saw their revenues effectively drop 80% or more in 2020 as the result of lockdowns — a challenge made all the worse given their relatively high fixed costs from leases and other occupancy expenses. By way of example, leading US operator Cinemark saw its EBIT swing from $400m in 2019 to -$600m in 2020. Unsurprisingly, COVID was the nail in the coffin for some theatres (at least for their equity holders). But some did in fact endure.

With lockdowns now well behind us, the live question between bulls and bears has turned to whether we will ever see the industry recover to what it was prior to 2020. The contours of the debate are well summarized by this passage:

“Patronage at movie theaters this year is expected to be down…but, because of higher ticket prices, total box-office revenue will decline somewhat less sharply…Hollywood's optimists insist that the decline in patronage is a temporary one, resulting from the coincidental release of a few poor movies. Others see in these statistics the evidence that the American film industry is approaching a crisis, the exact nature of which can't yet be known.”

On its face, we can see that there are really two strains of arguments coming from the bulls. The first relates to volumes and asserts that depressed attendance levels are a function not of secular changes in consumer behavior, but rather of the quality of content, which cyclical and merely in a downturn. The second relates to price and posits that notwithstanding structurally reduced attendance levels, the industry should be able to offset volumes with higher prices. I agree with both of these positions and will spend some time arguing in support later on.

Before we go there, however, I think there is something even more interesting about that excerpted passage: viz. that it was written, not in the COVID aftermath, but forty-years ago by the great film critic Canby in an effort to grapple with the perceived threat to the box office posed by the…VCR.

The more things change, the more they stay the same.

Indeed, what we learn from a review of the history of film exhibition is that the live debate regarding the health and future of the industry is nearly as old as the industry itself. But even more than that, we can see that both sides of the argument have been correct. On one hand, viewed as the percentage of Americans attending the movies weekly, film exhibition actually peaked as far back as the 1930s during the Golden Age of Hollywood. In fact, to this day, 1939’s Gone With The Wind remains the highest grossing film of all time on an inflation adjusted basis. To put some numbers on it, ~65% of the US population attended the movies weekly in 1930, with that number persistently declining each decade, to what is low single digits today. So understood, the bears have been right about cinemas structural decline for coming up on a century now.

And yet, despite the waning primacy of moviegoing to the average consumer and the endless forms of entertainment competing for our attention, it’s notable that half of the top dozen grossing films of all time were released after 1990, and three of the top ten were released well into the 21st century. This idea implied in the Canby excerpt that attendance is a function of content quality is hard to dispute and, as we will see, appears as true today as it ever was. The great film producer Robert Evans long ago made a similar observation, which succinctly threads these two viewpoints: “Moreover, where people had once seen going to the movies as an exciting outing, regardless of the film itself, now they went to see a particular movie…”.

If you build it, they will come.

Of course, the reality of secularly declining attendance does not per se tell you everything about the health of an industry, and such information certainly has limited use from an investment standpoint. So it’s therefore worth noting a couple fascinating dynamics (the timeframes on these data points is scattered, but remember, the percentage of people attending movies weekly has declined every single decade since the 1930, so all these statistics arose in spite of that):

The total number screens in the US effectively doubled from 20,000 to 40,000 between 1980 and 2007.

The number of films released theatrically on annual basis historically trended up and to the right until COVID.

Revenues and profits of many publicly traded cinema companies peaked in 2019.

So what’s going on here? What explains the rise in film count and screen count overtime? And how did listed cinema companies manage to generate record profits in 2019? (After all, hadn’t the final nail in the coffin, streaming, become ubiquitous by then?)

The obvious answers to these questions are that absolute population growth and price taking have counter-acted declines in relative demand. At least in nominal terms, box office revenues have been supported by ticket prices effectively tripling over the last 30 years (with similar price hikes at concession stands also helping). But the more interesting finding is that the number of tickets sold in the US in 1995 was essentially unchanged by 2019 (~1.2 billon), which is the floor of the range of sales for each year in between, with just over 1.5 billon being the high.

While, admittedly, 2019 ticket sales were ~20% lower than the peak in 2003, I suspect most readers would be surprised to see how stable volumes over this period were, particularly given the mass proliferation of a pretty disruptive technology called the internet during this period, and all the low cost ways it competes for our attention.

So what I want to consider next is how this 100 year old form of entertainment — viz. paying money to sit in front of a screen to watch a movie — has managed, at least up until COVID, to sell over a billion tickets annually in the US alone while charging the customer more and more every year, despite all the novel technology and media vying for our attention, including media that offer more convenient and low cost ways of watching the exact same films. How has this industry endured despite the endless existential threats? The answer is evolution through cycles. The exhibition industry and its relationship to the consumer has been evolving for decades — but cinema itself is forever.

Another apt passage from the archives before we get into it:

“The history of technology, perhaps more than any other kind of history, is full of premature obituaries,” observed Library of Congress historian Daniel Boorstin a few years ago. “We are prone, especially in this fast-moving country, to what I call the ‘displacive’ fallacy--to believe that every new technology displaces the old technology; that television will replace radio, that electronic news will displace print journalism, that the automobile will displace the human foot and that television will replace the book. But each of these new technologies has simply given a new role to the old technologies.”

A Brief History

As noted, the percentage of Americans going to the movies peaked in the 1930s. What happened?

The initial decline in relative attendance following the Golden Age is often attributed to technological disruption — i.e. to the birth of television. However, while television no doubt permanently changed our relationship with the movies, it does not solely explain the precipitous declines in 1940s, given the TV did not become ubiquitous in US households until the 1950s. A likely explanation lies in suburbanization and the consequent migration of the population away from urban theatre houses.

The studios and cinemas did the best they could to respond to these radical changes. On the exhibition side, the multiplex was spawn, providing improved access for suburbanites, as well optionality around which film to watch and what times to watch it. On the studio side, efforts were made to compete with TV through big-budget productions (‘blockbusters”), audio and visual technological advancements to improve the experience like Technicolor and increased aspect ratios, and exploring mature subject matter not fit for TV. Ultimately, competition from television ushered in a world where “going to the movies” was replaced with “going to see a particular movie”.

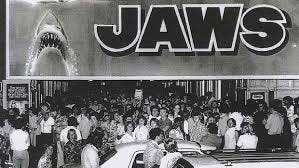

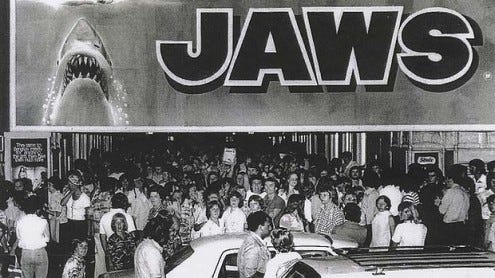

Recognizing the need to produce quality content to generate demand, studios eventually relinquished control to ambitious auteurs, leading to the age of New Hollywood from the late 60s through the 70s, defined by innovative and challenging films which escaped the formulaic shackles of the studios. This movement eventually culminated (or terminated, depending who you ask) with the summer blockbuster, with major hits like Jaws and Star Wars.

The 1980s then saw the widespread adoption of the VCR, which was in 1/3 of US homes by 1985. This challenged the box office in at least two ways. Most obviously, it made abundant films titles available for rent to be viewed from the comfort of one’s home. Surveys at the time found that movie theatre attendance dropped consistently in the middle of the decade for people that owned VCRs.

But the more pernicious consequence of the VCR was that it fractured the longstanding incentive alignment between studio and exhibitors. Studios, learning from their mistake in trying to compete with television, sought to embrace this new technology and soon discovered that they could earn profits through the rental business. This spurred a trend towards the production of more films, of a largely ‘disposable’ flavor — the birth of endless sequels and recycled IP that still permeates the industry today. Here is Canby again in 1985:

The ''new'' movies? They're already here - the pre-sold, would-be mass-market entertainments that are spinoffs or sequels of previous hits, or that contain elements - either in casting or story material - that make them immediately identifiable to the public.

Without well-publicized theatrical runs to introduce them, the films of the VCR age will play it increasingly safe, like the series shows on free television. They'll be dramatized trademarks, sometimes designer-label movies. Get ready for ''Rocky 16,'' ''Death Wish 8,'' ''Back to the Future - AGAIN'' and ''Steven Spielberg's Extra-Sensory Deprivation Tests.''

Due to become more and more scarce are those films that, like ''Kiss of the Spider Woman,'' ''Stranger Than Paradise'' and ''The Gods Must Be Crazy,'' have no so-called presold values and depend on long runs in a single theater to build interest.

Increasingly vertically integrated major film studios in Hollywood, believing they found a formula for success in the late 70s blockbusters, wrestled back creative control, dispensed with the auteurs, and focused on big — big budgets, big stars, big effects. This homogenized, formulaic film making eroded the quality of the box office slate, while the growing volume of direct to video, independent films from talented directors who didn’t fit the mass-market mold gave consumers less reason to go to the theatre. At the same time, higher production costs for these big movies squeezed the margins of exhibitors.

But things soon course corrected and these perceived challenges turned out to be opportunity. Indeed, box office numbers actually reached new highs as the 80s wore on, with a common explanation being that increased exposure to movies at home increased people’s love for filmgoing in all its forms:

“Exhibition had survived despite countless doom-and-gloom predictions in the past… Jack Valenti noted in 1982 that while some 40 percent of television homes were equipped with cable, 18 million subscribed to pay TV or cable movie channels, and 4 million video recorders were in the nation’s living rooms, the year had still recorded an all-time-high box office record. The reason behind this, he argued, was simple: People who love movies love them in every medium.”

“The studios, to their great relief, have found that home video, like the discount fares offered by airlines, brings in new business, and that people who develop a fondness for watching movies on videocassettes do not, by and large, stop going to movie theaters. Some industry insiders go even further; they suggest that home video, by turning more people on to movies, has actually increased the potential audience for theaters as well. And in the first three months of 1987, movie theater revenues ran ahead of 1984--a year in which the theatrical side of the industry, for the first time, earned more than $4 billion.”

Disruptive technology, initially perceived as an existential threat, turned out to be a blessing. A lesson worth keeping in mind as we go along.

Moreover, faced with these disruptive undercurrents, capitalism did its thing and forced exhibitors to evolve their offering. The circuit by the mid 1980s was poorly maintained and antiquated. In an effort modernize the offering and draw audiences, a new style of cinema emerged: out with the multiplex, in with the Megaplex. Unlike the multiplexes of the old word, which were often in malls, the megaplex was an enormous standalone venue with state of the art visual and audio technology (e.g. IMAX screens and Dolby Sound systems), as well as improved concession offerings and seating (viz. stadium seating). The ambition was obvious: to give people a reason to pay to watch movies that would soon be available for a lower price tag at home.

From an economic viewpoint, operators envisioned Megaplexes offering both scale benefits (spreading fixed costs across multiple screens) and the ability to match supply and demand (e.g. by screening films with less demand in smaller auditoriums) without reducing viewing options.

At the outset, there was a mutual benefit shared between Multiplexes and the emergence of independent, but commercially appealing cinema from studios like Miramax, whose films were able to fill out capacity not consumed by major blockbusters. The quality of content went up in 1990s, with the 80s still often regarded today as a low point for the art form:

“Films became more varied and a larger share of them started coming from original ideas, rather than from sequels, remakes, or adaptations. Suddenly the major studios were throwing money at new ideas and new directors. Creative new indie movies—the type of which used to live only in small arthouse theaters— started getting a wider release.”

Recognizing the success the early Megaplexes were having, development accelerated, and the US screen count jumped from 23,000 in 1988 to 37,000 by 2000. Operators, feeling the pressure to compete, took on piles of debt to finance construction. You can probably see where this is going…

By the end of 1990s the Megaplex boom resulted in far too many screens to fill — the 60% increase in screen count through the decade was met by only a 36% increase in admissions. These theatres accordingly suffered from negative operating leverage and the losses spiraled out of control. Major operators, having aggressively levered up to participate in the boom, saw their debt downgraded. Eventually, in 2000, eight of the major US cinema chains declared bankruptcy, including United Artists Theatres, Silver Cinemas (Landmark), and Carmike. Then the big fish, Regal, at the time the largest operator in the US, filed in 2001.

But distress breeds opportunity and it did not take long for gutsy financial players to step in and start consolidating the remnants. Philip Anschutz and Oaktree took control of Regal, which was merged with United Artists and Edwards. AMC acquired General Cinema and Gulf State theatres, and would later merge with Loews in 2006. By 2007, the top 4 US theatre chains controlled 62% of the market. The number of theatres declined, while screen counts remained relatively flat. The remaining players, rather than growing their screen counts, focused on digitizing their offering and building out premium large-format (PLFs) auditoriums (e.g. IMAX).

And that brings us to the 2010s — a decade that can really be summed up with two words: streaming and Disney.

Like the VCR and television before it, the proliferation of streaming services in the early 2010s was initially perceived as yet another existential threat to movie theatres. In addition to providing consumers a virtually endless catalogue of films that could be viewed effortlessly from home, streaming also led another moment of divergent incentives between studios and exhibitors. In this case, the streamers became the studios, with Disney developing its own streaming service, and companies like Netflix, Apple, and Amazon now developing their own content and either distributing it direct to their streaming platforms, or concurrent with truncated theatrical windows. The impacts on box office attendance were material in the mid 2010s, with average tickets sold per person declining from 4.1 in 2010 to 3.8 in 2015, and overall attendance hitting a 20 year low in 2014.

As usual, however, the impact of this disruptive technology was difficult to disentangle from the quality of the film slate. The 2010’s saw enormous consolidation amongst distributors, with Disney acquiring Marvel and Lucasfilm (Star Wars) early in the decade, and eventually 20th Century Fox. By the end of the Decade, Disney controlled 40% of the domestic market and the box office effectively turned into an outlet for its IP. While Disney would eventually deliver monster hits like Avengers End Game, the first half of the decade was plagued an endless string of forgettable blockbuster sequels from franchises like Transformers, Hunger Games, and on and on.

“It was the era of mega-franchises, of superhero movies and blockbuster IPs that championed universal ideas and themes. Conversely, midbudget films were increasingly struggling to compete, frequently finding homes on streaming platforms. As the studio system adapted its stories to cater to vast global audiences, the global box office responded accordingly. With fewer movies accounting for larger percentages of annual revenues, the international marketplace brought profitability to domestic flops.”

These franchises did, in fact, draw large crowds to the box office when done correctly. But the box office became blockbuster hit driven, resulting in smaller Megaplex auditoriums going unfilled. And if those occasional blockbusters did flop, the entire box office would sink with it. Given the enormous costs of producing these films, the quantity of releases from the six major studios declined significantly from an average of 112 annual to 83 during the 2010s. For cinemas, that left a ton of whitespace to fill. Meanwhile, the auteurs were relegated to home video yet again.

But then — you guessed it — the exhibition industry evolved to meet the moment.

Major cinema operators expanded through M&A, leading to further consolidation, now at a global scale: AMC acquired Carmike, adding 2600 screens in the US, while also entering Europe through its acquisition of Odeon; UK player Cineworld, meanwhile, purchased Regal. The big three of AMC, Cinemark, and Cineworld (Regal) controlled more than 50% of the domestic market by the end of the decade, as well as boasting large global footprints.

Operators also invested heavily in modernization. Ticketing became digitized, making the process of selecting showtimes and purchasing tickets much more convenient for customers, while also reducing opex through reduced headcount needs. They also used online ticketing to improve loyalty programs and promotions, as well as to collect data on customer patterns and preferences to enable targeted marketing campaigns — something previously delegated to distributors. Perhaps the most important shift that arose during this period, however, was the shift to ‘Premium’: stadium seating was replaced with luxury recliners, concession offerings were vastly improved, with in-seat service and alcohol often available, and large format screens were increasingly installed to match the needs of the slate (i.e. large action movies). Apparently, the number of PLF auditoriums doubled between 2014 and 2017.

All of these changes helped cinemas drastically increase average spend per patron, as sales shifted towards VIP offerings. The results can be seen in the financials of public issuers during this period, with sales and EBIT largely trending higher as the decade went on.

Finally, the same two phenomena that happened with VCRs happened again with streaming. First, rather than shift consumer preferences away from movie theatres, it actually helped to reinvigorate and expand the consumer’s interest in cinema. Indeed, a 2018 study by EY found that those who engaged in streaming more were also more likely to go to movie theatres, suggesting that the two forms of consumption are complementary rather than competitive. Second, studios, after first attempting to bypass theatres on the belief that they could earn better returns by going direct to streaming, quickly realized that theatrical releases are essential for marketing films and capturing a sufficient audience (especially given new films now have to compete with streaming catalogues that encompass the entire history of digital entertainment):

“Streaming is an important part of a film’s distribution plan, but it does not replace theaters which remain primary in the film ecosystem. We learned there cannot be billion-dollar movies without movie theaters. Without billion-dollar movies there cannot be $200 million budgets. Films just are not as majestic or compelling if they have not opened in a movie theater. That is why, after the failure of day and date releases (which cannibalized both theatrical and streaming revenues), the studios, including those which sent their entire slates (Warner Bros.) into simultaneous release, quickly shifted and announced their films would open ‘only in theaters,'” the report concluded.

The 2010s ended with a bang, as box office receipts globally exceeded $42B for the first time, lead by Avengers End Game, which became, for a moment, the highest grossing film of all time in nominal terms.

Ultimately, it was the same story we’ve seen time and time again: despite perceived doom from technological innovation, cinema defied the odds and did not die. Rather, it thrived.

Then came the biggest disruption of all.

COVID and The Road Ahead

You may be wondering by now: why did you just give a decade by decade summary of film exhibition history? Because I think an interesting insight emerges from this review that may be very instructive in building an investment thesis in this largely neglected and contrarian sector in a post-COVID world.

Specifically, it appears to me that there are at least four separate but related cycles that have played out repeatedly throughout the history of the movie theatre business:

The capital cycle: the industry over invests (e.g. 90s Megaplexes) but eventually right sizes to meet demand be it through reduced screen counts or M&A (e.g. 2000s consolidation) and weathers economic challenges by investing in new technologies and experiences, which generate surprisingly high returns on capex in later years (e.g. 1950s Technicolor, 1990s Dolby sound and stadium seats, 2010s shift to premium, etc.);

The content cycle: studios produce successful blockbuster films and, excited by the results, they recycle the same formula and IP over and over until the consumer inevitably grows fatigued and uninterested (e.g. 1980s blockbusters, 1950/60s Hollywood). In need of something new, studios relinquish content control to auteurs who give consumers something fresh to be excited about.

The cultural cycle: consumer interest in film generally (as well as preference for medium and variety) ebbs and flows, but tends to be reinvigorated by new technologies that improve accessibility (e.g. the surge in box office numbers after the VCR and streaming).

The industry alignment/misalignment cycle: new technologies disrupt and fracture the symbiotic relationship between studios and exhibitors, only for them to later recognize that they need each other (e.g. post VCR and streaming).

Each of these cycles are interrelated: e.g. the cultural cycle drives content and vice versa.

The reason I find this sector fascinating right now is that I believe we are presently on the right side of each of these cycles and that the market is still largely asleep on this because the century’s long narrative that the “industry is dying” hit its apex is 2020 and has not been revised in the face of clearly conflicting evidence. Moreover, the clear recovery happening in this multi-layered cyclical pattern has been masked by the 2023 Writer’s Strike, giving the lazy observer enough to accept bearish consensus.

So where are we in these four cycles and what is this ‘narrative conflicting evidence’ I speak of?

The global closure of cinemas in 2020, though devastating for the industry in the short run, has done wonders from a capital cycle perspective. In the US, the screen count has declined more than 12% from 2019 and that number has been trending down. The big three now control ~53% of the US, including 15% by Regal, whose parent Cineworld emerged from bankruptcy in 2022, in a restructuring process that involved the closure of many theatres (and concentration is actually more pronounced in other countries, such as Canada, where Cineplex controls ~75% of the market).

Rather than investing in growth, operators have been focused on right sizing their complexes and upgrading them to higher price point premium formats: as of 2024, over 950 theatres in North America were PLFs, a 35% increase from 2019, while these auditoriums are capturing more than 15% of the box office, compared with 10% prior to the pandemic. These investments, along with investments in concession offerings, have helped drive huge increases in per patron spend — e.g. premium tickets have helped CNK’s average US ticket prices trend from $8.43 in 2019 to $10.08 last quarter, while average concession spend has grown from $5.35 in 2019 to $7.98 today. Meanwhile, operating expenses have been aided by leverage over landlords and higher efficiency technology that has helped reduce costs, e.g., utility bills.

In short, supply is shrinking but quality is improving.

From a content cycle perspective, the trend is clearly in the right direction. Just this week, the WSJ reported that Disney/Marvel is actively looking for a reset, recognizing that the consumer has grown fatigued with its content. While sequels and formulaic blockbusters are still rolling out (e.g. the 91st Jurassic Park movie), a look at the content ahead indicates a much healthier, balanced slate that includes mainstream independent films and auteur projects, such as upcoming films like Bong Joon-Ho’s Mickey 17 and Paul Thomas Anderson’s One Battle After Another. The slate looks perhaps even healthier the following year with Christopher Nolan’s Odyssey and the third installation of Dune.

As you can see, both the number of films being released is on an uptrend (important for screen utilization/variety) as is the share of films being released outside of the major studios:

Readers should note that output during 2023 and 2024 was materially impacted by the Writer’s Strike. This caused a significant headwind for the box office during those years which I believe many are mistaking as confirmatory evidence of a permanently altered consumer, rather than the content simply not being there. There is strong evidence in support of this being content driven, which brings me to the state of the cultural cycle.

Despite the soft numbers the industry has seen since COVID, consider the following:

The “Barbenheimer” phenomenon in 2023 resulted in the fourth-largest weekend ever at the US box office;

2024’s Inside Out 2 became the highest-grossing animated film of all time;

2024’s Wicked became the highest-grossing Broadway adaption of all time;

2024 saw the largest Thanksgiving box office in history;

China’s Ne Zha 2, released in late 2024, has recently become the 5th highest grossing film of all time globally.

Minecraft, which debuted this year with modest expectations, is now the 100th highest grossing film of all time, as well as breaking the opening weekend record for a film based on a video game.

Are these just outliers?

Well, Cinemark just announced that it expects 2025 attendance to reach 90% of pre-pandemic levels. I think it’s pretty clear we are at the right point in the cultural cycle: if the content is right, people are as willing to go to films as ever before.

Finally, the “alignment” cycle. As I noted earlier, the enormous competition for eyeballs due to consumers being able to stream any film ever made has been a firm reminder of the importance of theatrical releases to having a successful film. Exhibitors and studios are as aligned as they have ever been. But what’s interesting this time around is that a new cog in the ecosystem — the streamers — are also aligned in having theatrical releases. The reason is simple: everyone makes more money when films get a theatrical release. Here is the NY Times on the benefits that accrue to streamers:

But the industry has now largely come to a very different conclusion: The key to making a movie a streaming success and attracting new subscribers is to first release it in theaters. It turns out that all the things that make theatrical movies successful — expansive marketing and public relations campaigns, and valuable word of mouth — continue to help movies perform once they land in the home.

An Attractive Investment Case?

So to conclude here, I want to lay out the investment case for the sector broadly. We are on the right side of the ‘four cycles’:

Screen counts are down, but quality of the offering is up. (Seriously, if you haven’t been to a remodeled IMAX auditorium, I think you’ll be very surprised about how much the experience has changed in 10 years). With reduced competition in a very consolidated space, diminished supply and uneconomic newbuilds, and pricing power driven by already incurred capex, the table is set for attractive ROICs, assuming demand is there.

Demand is there. Content quality is going up, as is the quantity of productions. And despite prevailing narratives that cinema is dead, the numbers tell a very different story.

The incentives are aligned across the industry to have a healthy box office.

Finally, we are in a precarious macroeconomic backdrop. Do you know what sector has historically held up very well in recessions? You guessed it:

The final piece is valuation, which I will say more about in the next piece when I highlight the actual company I want to pitch. But broadly speaking, I think it’s clear that companies in this ecosystem are incredibly mispriced, for the simple reason that COVID led to a mistaken narrative that cinemas are dead and that the clear ongoing recovery of the industry has largely been masked by the (now rolling off) impacts of Writer’s Strike. Pick any name in the sector (ignore AMC for obvious reasons) and you’ll likely see it trading well below its COVID highs. Then, take a close look at the trajectory of its business and ask yourself if that really make sense.

Ultimately, I think there is a lot of money to be made here because the market has missed an important history lesson: cinema is forever.

Really interesting read!

you can summarize the whole article with 6 words : " people like going to the movies".

going to the cinema is not to watch a movie , its a way of recreation.